We're Quickly Losing Our Need To Read

Now that the media superhighway delivers every kind of content on equal terms, people want to take in words with their ears, not their eyes.

Some thought the Internet would spread reading and writing everywhere. A Stanford professor talked about a “literacy revolution” online.

The One Laptop Per Child project was going to teach millions of children to read. Households would own multiple Kindles, and e-books would overtake paper ones, Amazon’s boss predicted.

Instead, as infinite bandwidth pipes video, audio and text almost interchangeably, humans are returning to nature, gathering information in the way that evolution created just for them: speech.

Half a billion people now listen regularly to talking podcasts — a development predicted by nobody. Indonesians and Romanians are especially keen. Audiobook sales are growing by double-digit rates while those of e-books and printed books are flat. My wife, a lifelong reader, now consumes books almost exclusively by listening.

Listening to prose or poetry takes about twice as long as reading it. Nevertheless more and more of our words arrive in the way of antiquity, when tales were told at the hearth, when literacy was rare and when reading silently to yourself was weird.

Users of the WhatsApp and WeChat texting apps now send “voice notes” that spare them from typing and reading. Slack began as a way to organize office emails but added audio and video “clips” because colleagues wanted to yack.

Online speech exploded in the pandemic because people preferred talking on Zoom and Teams to endless messaging. TikTok and Reels are overwhelmingly oral and pictorial. The New York Times just added a “Listening Tab” to its app if you don’t want to read the articles.

In Orality and Literacy, Walter Ong reminded us that writing is a technological tool like the automobile rather than something innately human. We started using little glyphs to represent spoken words about 5,000 years ago. Printing, arriving in the 1400s, tightened writing’s hold on language and changed how people thought.

Ong acknowledged that radio, TV, telephones and other gadgets were bringing “the age of ‘secondary orality.’” (This was in 1982.) But he saw telecommunication as a sideshow. Electronic speech, he wrote, is “based permanently on the use of writing and print, which are essential for the manufacture and operation of the equipment and for its use as well.”

Maybe. The twist is that technology has blown past anything Ong could have imagined. Writing was revolutionary because it made words storable, retrievable, scannable and shareable, he wrote. Guess what? Computers and the Internet now enable all those features for speech.

Even the highest form of textual experience — immersion in a great novel — doesn’t depend on reading, it seems. Fiction dominates audiobooks.

Artificial intelligence is eliminating writing jobs. AI composes ad copy, legal briefs, news stories, school lessons, drama scripts and office presentations instantly and essentially for free. Often these are rendered into speech.

Any humans still left in the office will supervise the AIs by talking, not by writing. Employees can already deal with email entirely through the spoken word, listening to speech summaries and replying in kind. ChatGPT’s Voice Mode “feels like AI from the movies,” claims OpenAI’s boss.

The hated “doctor at the laptop” awkwardness is vanishing as AIs summarize patient conversations and put them in the electronic chart. Clinicians query the chart by speaking and it replies the same way.

Writing is still part of these processes, logging and storing the spoken words. But it’s inside the machine, not for human reading but for generating output in the manner of punched paper rolls in a player piano.

You who are reading this reject the idea that reading will become less important. So do I. “Our text-bound minds” as Ong calls them, can’t imagine society without it.

But since the 1700s or so the future has turned out mind-blowingly different from what anybody expected. Book reading is already declining, especially among young people. Unpromising government-subsidy programs are now attempting to support books as well as babies.

Our grandchildren will still teach their children to read. But what about after that? With writing automated, many remaining jobs will involve working with things and working with people, neither needing high literacy.

Illiteracy in 2150 might be like not knowing Latin in, say, 1600 — nothing to be proud of, but no sure barrier to education, career and status. It might make people less informed and shrink the life of the mind. But it will also redefine what it means to be educated and awaken old cognitive skills.

The internet has sprung a thousand years of pent-up demand for spoken stories, lectures, sermons, conversations, reporting, confessions and ranting. Are we “evolving toward an oral culture,” as Tyler Cowen suggested in a conversation with David Brooks posted a few weeks ago?

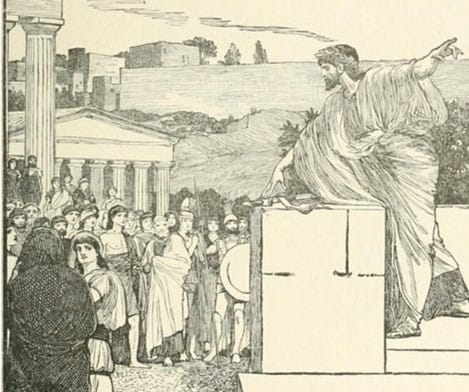

Socrates suggested, in Plato’s Phaedrus, that writing is a crutch, atrophying memory, mind and discourse. Societies in the age of tertiary orality will build new speech cultures, this time with machines instead of bards. Already people are learning how to maximize speech comprehension by speeding up podcasts.

Writing began as a registry for accounts, laws and scripture. Maybe it will revert to that, with literate savants in the reference section maintaining the source texts and some sort of blockchain setup ensuring nobody hacks the audio Gospels. Ted Gioia suggests that printed books will be the future’s last secure data center. But who reads data centers?

Ong called writing “technologizing the word.” Now technology is leaving writing behind as if it were so much Morse code.

I published a version of this last week in The Washington Independent Review of Books.

I was just thinking the other day of how little I read books anymore. Listening and watching are pushing reading to third place. Thanks for your analysis. At least someone is still thinking and writing!

Count me among those folks who has shifted from reading with my eyes to "reading" with my ears, but let's not rush to consign audiobooks into the same technodystopian slop bucket as AI-written (or read) text. A quality audiobook read by a human (probably an actor for fiction or preferably the author for nonfiction) is a natural extension, you might even say enhancement, of the written form; AI-narrated audiobooks are the same junk as those AI-written pieces that hallucinate books. I'll admit my shrunken attention span is responsible for my shift to audio, but if I'm reading more--and taking the words in just as effectively--who's losing out?