She Resurrected The World of Henry VIII

Lacking a professorship, with little academic or financial support, Muriel St. Clare Byrne produced one of the great works of English history scholarship.

I was thrilled to write this for How-to History, which gives an insider look at the craft of uncovering and understanding the past.

On 6 Nov. 1538, a woman in her late 40s named Honor Lisle boarded a ship at the stair of Calais. She hoped to meet her husband, Arthur Plantagenet, Viscount Lisle, at the docks, but failed. This upset her. The wind was light. The vessel didn’t reach Dover until 10 p.m.

She told “merry tales” to her attendants and the captain, named Lamb, while cooks made a shore supper. In the dark Lamb had crashed the ship into a pier, breaking the bowsprit. The next day she left for London and an attempted meeting with Henry VIII. She wanted the king to fix a property lawsuit in her favor. She missed her husband. “I shall think every hour ten till I be with you again,” she wrote him.[1]

We know all about the Lisles. We know about their beautiful daughters, their overworked servants, their friends and enemies, their money, their rich meals and garments, their fears and sicknesses and sleeping habits. We watch through the 1530s as they navigate mortal Tudor politics and Lord Lisle moves closer and closer -- as we know but he doesn’t -- to arrest and imprisonment in the Tower.

We know the Lisles because a remarkable historian named Muriel St. Clare Byrne spent a lifetime deciphering, transcribing and analyzing their letters, moving to Tudor England in her mind and living with them like family.

The University of Chicago Press published the Lisle Letters -- 1,677 documents in a million words, plus a million words of commentary by Byrne, in six volumes -- in 1981.

Written or dictated by dozens of correspondents, sent mostly between London and Calais, mentioning hundreds of characters, they had been seized as evidence of possible treason in Lisle’s case and then mostly forgotten. Lisle was a bastard of King Edward IV, an uncle of Henry VIII and Lord Deputy of Calais, England’s last scrap of territory on the continent.

“One of the most extraordinary historical works to be published in the century,” said The New York Times.[2] “We can really hear the people of early Tudor England talking,” said The Sunday Times. Commentators made comparisons with the works of Tolstoy, Proust and Pasternak.

Even the most enthusiastic reviewers didn’t rave enough about Byrne’s personal accomplishment. How, without a professorship, living “at the margins of elite academic life,” [3] with almost no help or supervision, did she produce what Smithsonian magazine called “a landmark of 20th century scholarship”?

Papers at the University of Chicago Library, where I spent a recent afternoon, show a determination and adoring love for her subject that carried her through decades of uncertainty, slights and money shortages and then a brutal rejection when she thought she was almost done.

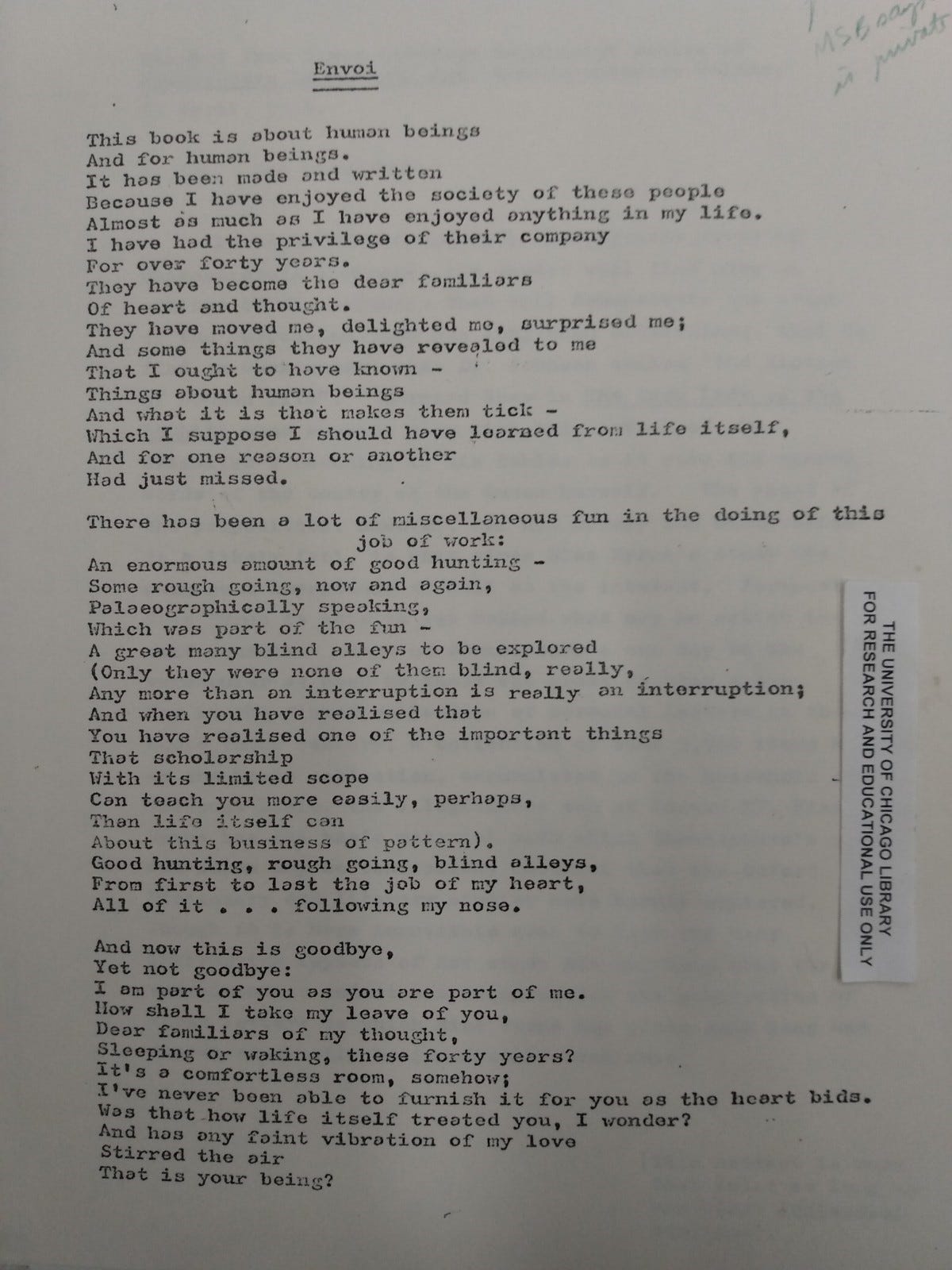

“I have enjoyed the society of these people/ Almost as much as I have enjoyed anything in my life,” she wrote near the end of the project in an unpublished farewell to the Lisles in the library’s Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections. “I am part of you as you are part of me. / How shall I take my leave of you, / Dear familiars of my thought, / Sleeping or waking, these forty years?”[4]

Byrne came across the Lisle Letters in the British Public Record Office in 1932. She had earned a master’s degree from Oxford’s Somerville College, making lifelong friendships described by Mo Moulton in The Mutual Admiration Society: How Dorothy L. Sayers And Her Oxford Circle Remade The World For Women.

But Byrne’s gender and lack of a first-class honors degree kept her from becoming a university don. She took temporary teaching jobs and wrote popular history, publishing Elizabethan Life in Town and Country in 1925 and earning money from a 1936 detective play she wrote with Sayers.

During World War II she had to duck under the Public Record Office tables and abandon the Lisle research if bombers threatened. Her lover and lifelong partner, Marjorie Barber, knew Byrne would be spared for the Lisles. “I think you will be kept to finish them, like Churchill,” she wrote.[5]

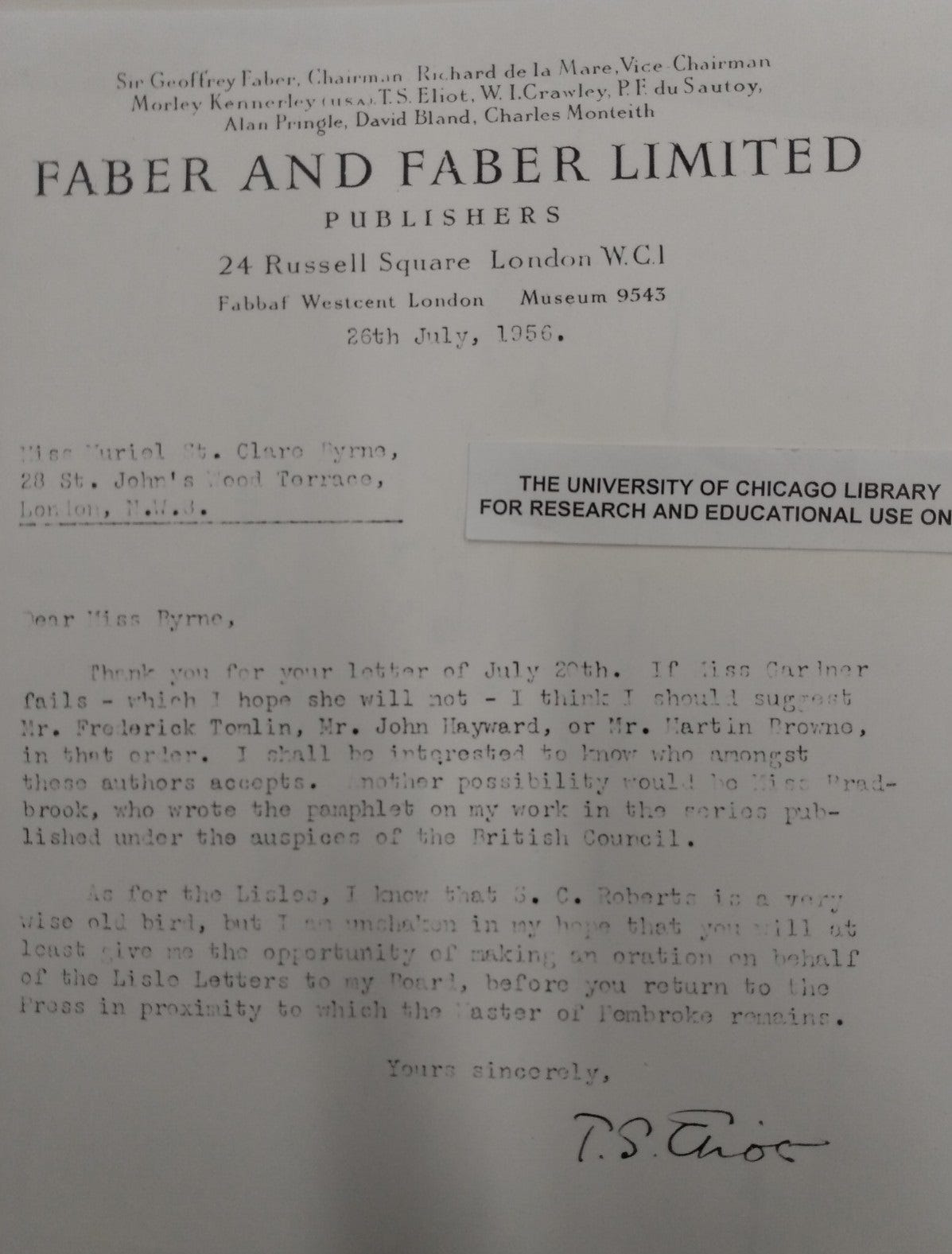

By the 1950s Byrne was talking about publishing. “I am unshaken in my hope that you will at least allow me to make an oration on behalf of the Lisle Letters to my board,” T.S. Eliot wrote to her in July 1956.[6] The poet was an editor at publisher Faber and Faber.

“I am indeed delighted that we shall now get the Lisle Papers published,” historian G.M. Trevelyan wrote to her in 1955.[7]

“I rejoice that you are now quite fit again and eager to finish your great work,” historian J. Dover Wilson wrote to her in 1964.[8]

“The work… is now in its final stages,” wrote Prof. A.G. Dickens in 1966, after Faber had finally agreed to publish. (Eliot had died the previous year.) [9]

In fact Byrne was stuck in the sixteenth century, absorbed in “an enormous amount of good hunting,” as she wrote in her unpublished envoi, going down “a great many blind alleys… following my nose” and getting nowhere close to the final stages.

No character was too obscure or removed from the Lisles to track down, link to associates and size up for personality and handwriting. Every writer deserved to be able to speak again. No financial dispute was too trivial to be adjudicated four centuries later.

Few paleographical puzzles (vmlyst spells humblest and frydstokefysche means fried stockfish) went unsolved. Honor Lisle’s request to Queen Anne Boleyn for an overdress called a kirtle is traced and analyzed through nearly a dozen letters sent over the course of more than a year.

“It would be idle to deny that Miss Byrne nearly kills her subject with love,” said The New York Times review.[10]

Maybe. But Bryne’s immersion produced a deep understanding of early-Tudor society -- and “things about human beings” generally, as she wrote -- along with the confidence to guide readers through this world with brio and good sense.

Meanwhile she was living off of royalty crumbs and infrequent grants. “I note with sorrow her financial situation,” Wilson wrote in a draft recommendation for funds, in words redlined out of the final version. [11]

Faber editors were horrified when they finally realized what was going on. They backed out, quite confident that turning Byrne’s 5,700 single-spaced, typed pages into a book was not a promising business venture.

“When we made the original contract in 1965 we really had no clear idea of what the book was going to contain,” partly because of Eliot’s death that year, a Faber executive wrote a decade later.[12]

To the rescue came the University of Chicago Press, which had already been marginally involved and was better set than Faber to seek charity for the project. Press Director Morris Philipson did brave work, raising $100,000 (about $500,000 today), arranging for the manuscript to be hand-carried from London by an acquaintance of Byrne’s on TWA Flight 771 and persuading the Crown to grant publishing rights to the letters for £25.

Not least of Philipson’s contributions was working long distance with Byrne (“Dear Good and Great Lady…”),[13] who sought large and unreasonable changes in paragraphing and indentation. “Those changes that you argue for, over and over again, are not going to be made,” Philipson told her in 1978.[14]

The Lisle Letters came out in the spring of 1981 on Byrne’s 86th birthday. Now again she turned toward the past, this time in her own sumptuously printed, red-and-blue clothbound books.

“Whenever I see her she is turning over the pages, purring over the layout, the reproduction and placing of the illustrations, the perfection of the index, how pleasantly the volumes look and handle,” Byrne’s friend Bridget Boland, who edited a one-volume abridgement published two years later, wrote to the Press. “If you had known her in the dark days when Fabers suddenly backed down you would not think her the same woman.”[15]

[1] Lisle Letters No. 275. Lady Lisle to Lord Lisle, 7 November, 1538. Lisle Letters abridgement pp 310-311. Full volume pp volume 5, no. 1262

[2] J.H. Plumb, “Henry VIII Was The Man To See,” The New York Times Book Review, June 14, 1981, p.9.

[3] Mo Moulton, The Mutual Admiration Society: How Dorothy L. Sayers and Her Oxford Circle Remade the World for Women, Basic Books, 2019, p. 133.

[4] M. St. Clare Byrne, undated, Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago.

[5] Moulton, pp. 202-3, p. 222, p. 253.

[6] T.S. Eliot to M. St. Clare Byrne, 26 July, 1956, HHG Special Collections.

[7] G.M. Trevelyan to M. St. Clare Byrne, 9 May, 1955, HHG Special Collections.

[8] J. Dover Wilson to M. St. Clare Byrne, 11 Jan., 1964, HHG Special Collections.

[9] A.G. Dickens to a Miss Swainson, 28 April, 1966, HHG Special Collections.

[10] Plumb, NYT.

[11] J. Dover Wilson to unknown, 14 Feb. 1964, HHG Special Collections.

[12] Frank Pike to Morris Philipson, 3 Feb. 1975, HHG Special Collections.

[13] Morris Philipson to M. St. Clare Byrne, 17 April 1975, HHG Special Collections.

[14] Morris Philipson to M. St. Clare Byrne, 26 July 1978. HHG Special Collections.

[15] Bridget Boland to a Miss Richardson, 27 March 1981. HHG Special Collections.